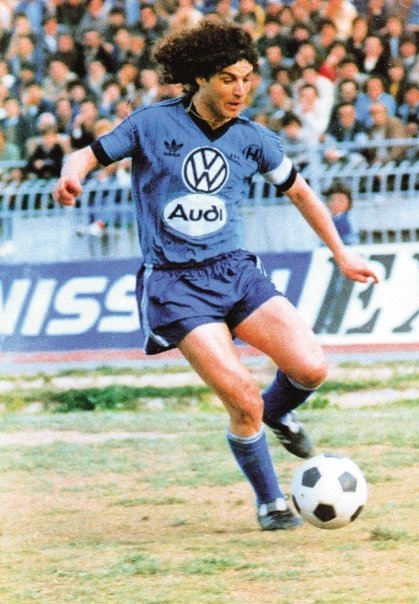

In 2003, to celebrate UEFA’s 50th anniversary, each European nation was asked to select a ‘Golden Player of the past 50 Years’. England’s was Moore. Germany’s was Beckenbauer. Holland’s was Cruyff. The Greeks, their’s was Vasilis Hatzipanagis. The Hellenic Football Federation opted for Hatzipanagis even though he never played a competitive fixture for Greece. Despite his brilliance, Hatzipanagis’s career became a myriad of ‘what ifs’, as he was denied numerous moves to Europe’s top clubs and the chance to represent his country. When a ‘World XI’ was put together to face the New York Cosmos in 1984 in an exhibition game, there were some well known faces on show. Beckenbauer, Kempes, Keegan, Shilton, Krol and Hugo Sanchez all among the impressive line-up. Having played out his entire career in footballing obscurity, Hatzipanagis’ genius was still recognised, as he took to the field alongside such esteemed peers.

Greece had a difficult start to the 20th century, and much of these troubles had a direct effect upon his family. The Greco-Turkish war set the tone, and Hatzipanagis’ parents were forced to move, becoming refugees. Greece became a dictatorship in the 1930’s, and soon saw itself suffering from Nazi occupation throughout World War II. Stability in the country never seemed likely; and after the war finished, civil war broke out. Once the civil war was over, in 1949, thousands of political refugees left Greece, with Tashkent and Alma-Ata (now Almaty), proving the most common destinations. It was at this time that Hatzipanagis’ parents moved to Tashkent, where he was born on October 26th 1955.

Tashkent was undergoing a number of radical changes at the time. One of the key cities of the Silk Road, Tashkent shook off that image as refugees flooded the city and began an industrial revolution. Any such progress was halted in 1966 when Tashkent earthquake devastated the city, destroying 80% of it. Out of this chaos though, a star was born. Dinamo Tashkent spotted the youngster training in a park, and offered him a contract, but Hatzipanagis chose to join Pakhtakor Tashkent instead, due to their impressive youth set-up. He was handed his debut at 17 against Shakhtar Donetsk, and remained in the first team for the next three years until he left the club.

With Pakhtador, Hatzipanagis quickly made a name for himself. He helped the club to promotion to the top flight in 1973, and was named the league’s second best player in 1974 and 1975, despite still being a teenager. It is worth noting that the man who beat Hatzipanagis to the award on both occasions was one Oleh Blokhin, who was also European Footballer of the Year and a Ballon d’Or winner in 1975; so no shame there. Hatzipanagis began representing the USSR at international level, first with the U-21’s and then the first team, before being chosen for the Soviet Union’s Olympic team of 1976, which won a bronze medal. Little did he know it, but these teenage year would prove the happiest and most productive of his footballing career. He was playing on the world stage and the USSR’s domestic league was relatively strong at the time.

In 1975, the possibility of a return to Greece opened up for Hatzipanagis and his parents. However, the move became very complicated. Soviet rules meant players were not classed as property, and therefore could not simply be bought and sold. Hatzipanagis already knew this as Olympiakos, the most successful club in Greece, had already tried and failed to acquire his services. His only option was to terminate his Soviet citizenship and apply for repatriation in Greece. Even that route was laden with complications though, Hatzipanagis’ family ties meant he was unlikely to be granted repatriation throughout much of Greece, and he was advised his only real chance would be where his grandparents had relocated to, in Thessaloniki. This of course meant finding a football team in the region.

Still only 20, Hatzipanagis joined Iraklis F.C. on a two-year deal. He had put his trust in an Armenian based in Moscow who oversaw the move, and would regret doing so for the rest of his career. The contract Hatzipanagis signed was open to a small piece of Greek legislature which stated that Iraklis could renew his deal every year for the next 10 years, effectively tying him to the club for the rest of his career. In 1975, having inspired a markedly average Iraklis team to Greek Cup victory, Hatzipanagis took the club he was still playing for to court. He won, but Iraklis took the matter to a court of appeal and won. Hatzipanagis was trapped.

The Greek league at the time was not a strong one, and Hatzipanagis was comfortably its star player. Interest in him continued to be high; with AEK, Lazio, Porto, Dinamo Moscow and Stuttgart all having offers waved away by Iraklis. In 1977, Hatzipanagis suffered a knee injury, and flew to London in order to receive treatment. The doctor he was assigned was the Arsenal physio, and as Hatzipanagis was nursed back to full-fitness, he began training with the Arsenal squad; who nicknamed him ‘Aristotle’. Even alongside the likes of Jennings, Brady and Macdonald, his class still shone through, and Terry Neill enquired to Iraklis with regards to signing the now 22-year-old midfielder, but Iraklis were having none of it.

Iraklis were essentially a midtable club, who hadn’t won a competition in 30 years before Hatzipanagis joined the club. They knew their ‘golden’ era was reliant upon him, moreover, they had become financially dependent on the skillful playmaker. Crowds would flock from across Greece to see the young man with a ball at his feet, and Iraklis couldn’t afford to let him go at any cost. This was most clearly highlighted when Panathinaikos bid £1.85 million for him at a time when Diego Maradona had just become the most expensive player in the world, joining Barcelona for £3 million. When this last offer was batted away, and now approaching his late 20’s, Hatzipanagis resigned himself to a career at Iraklis.

The misfortunes of circumstance which plagued Hatzipanagis’ career went further. Having represented the Soviet Union at international level, FIFA ruled that he could not also represent Greece. Despite all the troubles of his career, this was the one thing that hurt Hatzipanagis most. Even though he desperately wanted to play football outside of Greece, Hatzipanagis had Greek blood in his veins and regularly speaks of his sadness at never being able to play for his country. Still when he speaks today there is hurt in Hatzipanagis’ voice that he could never prove his credentials on the world stage with either club or country. He would have every right to be bitter, yet he seems regretful rather than resentful, admitting it was a mistake to leave the Soviet Union in 1975.

Hatzipanagis went on to play 281 times for Iraklis, over 15 years, hanging up his boots in 1990 after a UEFA Cup game against Valencia. To those who saw him, Hatzipanagis will always be one of the true greats, yet sadly, those people will always be limited due to a cruel and unfair contract. His father later revealed that when he and his mother moved to Tashkent, they almost moved to London. It is incredible to think what might have been had he chosen the latter. Hatzipanagis’ legacy is great in Greece, where he became known as ‘the Footballing Nureyev’, although it should of course have been much wider. As well as his magic on the football pitch, his numerous court battles resulted in the altering of Greek laws, which were sadly introduced too late to affect Hatzipanagis himself.

Truly one of the great footballers of all time. I had the pleasure of seeing him perform — yes, perform, not just simply play — when I was a teenager in the ’80s. Incredible dribble skills, superb field movement without the ball and extremely astute. Shame the world was not able to enjoy his game.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great comment Nuke, jealous of you having watched Hatzipanagis in the flesh. A great shame indeed.

LikeLike